We use cookies on this site to enhance your experience.

By selecting “Accept” and continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of cookies.

Search for academic programs, residence, tours and events and more.

Jan. 24, 2025

Print | PDFChris Nighman’s (History) research agenda lies at two important junctures in the history of communication—the transition from manuscript to print culture in the fifteenth century and the current digital revolution. He began to work in digital humanities about 25 years ago, when the field was still fairly new, when he started to edit a large Latin text and publish it on Laurier’s server. He then worked with computer scientists to develop an innovative search engine to access that text, and that research tool has enabled him to develop additional websites and print publications (nearly all of which are open access). At present he directs 12 academic websites for students and scholars of medieval and early modern Latin literature.

What follows is an updated version of an interview conducted by Eric Story, PhD (Laurier Centre for the Study of Canada).

Eric Story (ES): Could you give me a brief description of your research interests?

Dr. Chris Nighman (CN): My doctoral thesis in the 1990s was on a series of sermons that were delivered at a big church conference—kind of like an academic conference but of theologians, bishops and abbots—called the Council of Constance, which met from 1414 to 1418. It dealt with some big problems facing the church at the time, including heresy and the Papal Schism, where three men laid claim to being the true Pope. I was editing the sermons of Richard Fleming, an Oxford theologian who went on to become the Bishop of Lincoln, and I found that his interest in ecclesiastical reform was driven by the perceived challenge of heresy to church authority.

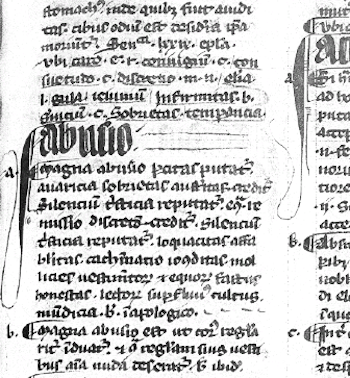

What also struck me in editing his sermons was his confidence in identifying quotes, for example, from Seneca or Augustine. These sermons were full of quotations. And the way he employed them reflected a certainty that these quotes were original. But, in fact, many weren’t. I realized that Fleming owned a copy of the Manipulus florum, which is a book of quotations. It means “a handful of flowers.” Each quotation is a beautiful blossom.

Anyway, when I searched through it, I found the quotations he had used. And many of them had been paraphrased, manipulated, miscited and changed in various ways. This opened up a whole new world of the transmission of authoritative quotations to me. The Manipulus is the most important of these collections of quotations—or florilegia—from the Middle Ages and had never been edited. I then thought that putting it online as an open access tool would be of great service to scholarship and the academic community. The initial edition work was from 2001 to 2013, but I’ve been revising it ever since.

ES: Let’s talk about the author of the Manipulus florum, Thomas of Ireland. What did you learn about Thomas when you were doing your research on the Manipulus?

CN: I didn’t actually learn that much about him that we didn’t already know. There was a messy historiography to grapple with when it comes to Thomas of Ireland. There were two Thomases from Ireland who had been conflated into one. One was a Franciscan and the other was a secular priest. In the late 1970s Mary Rouse and Richard Rouse determined that it was the secular priest who had compiled this florilegium at Paris. Other than that, he wrote three short theological tracts and taught at the Sorbonne. But what I found out about him is his attitude towards what he was doing—compiling a florilegium. The paper that I gave at the Manipulus florum colloquium I organized in 2014, which was published in 2019, is one of my revisionist contributions to the field. An old tradition claimed that someone named John of Wales had started the Manipulus florum and Thomas had finished it, though this idea was dismissed in the 1970s. Using the Janus search engine, which I’ll discuss later, I actually found that there were a number of lines from John of Wales that show up in the Manipulus florum because they accompanied quotations. However, I don’t think Thomas just used John of Wales’ book; I believe John started the Manipulus and then Thomas finished it. Thomas’ big contribution was to provide a cross-referencing system that was originally believed to have been invented along with the printing press but was actually invented much earlier by people like Thomas to make it easier for clergy to find specific pieces of information within a larger text.

ES: How do you identify as a researcher?

CN: Except for the online publication approach, I’m a bit of an old-fashioned scholar, I suppose. I consider myself to be a Latin philologist and an intellectual and cultural historian, but not in the sense of the “new cultural history” that began in the late 1970s. I look at changing intellectual world views in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance. When I teach the Italian Renaissance, I start in the late Middle Ages, and I argue that the Renaissance wasn’t so much a historical period as it was a cultural and intellectual movement that transitioned from the Middle Ages and into the early modern world. But it doesn’t stand as a period on its own because it was limited largely to the male, elite Italian class. It did eventually filter north, but it didn’t have the same broad impact as, say, the Reformation had on everyone.

ES: This is where your work using digital tools is important because it allows you to revisit old questions with an entirely new toolkit. When did you begin to realize the usefulness of digital methodologies in your research?

CN: In the 1990s, when I was editing Fleming’s sermons, digital was just beginning to enter the picture. I have to give credit where credit is due. One of my graduate school colleagues, Jim Ginther, who is now at the University of Toronto, came up with the Electronic Grosseteste. He was working on a thirteenth-century English bishop, scientist and theologian named Robert Grosseteste and built a digital repository of Grosseteste’s materials, bibliographies, non-copyrighted texts and other works. I remember looking at what he was doing and thinking, “Wow, this is where the field is going.”

When I mentioned it to my wife, she said, “Well, why don’t you do something like this?” I thought the Manipulus florum would be a terrific project for an online edition. At the time, I remember thinking I’d finish the Electronic Manipulus florum Project quickly, and then return to sermon studies and perhaps publish a book. But once I got into the digital humanities and realized its potential, it became almost addictive. As soon as I finished the first iteration of the online Manipulus florum, I starting work on another medieval florilegium, the Liber pharetrae—which means the “book of the quiver” such that each quotation is like an arrow aimed at exactly the topic one would like to address. I recently completed a third online edition of yet another medieval florilegium, Viridarium consolationis—which means “Garden of consolation”, where the compiler likens the collected quotations to fruit and flowers.

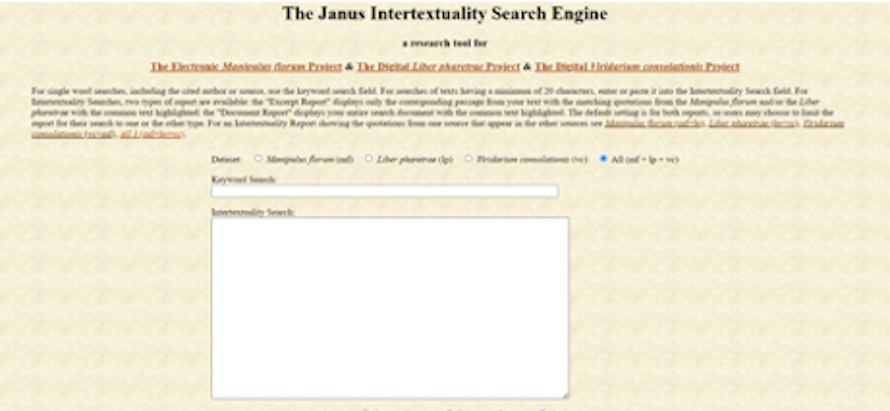

ES: You mentioned the Janus Intertextuality Search engine earlier. What is that and how does it relate to the Manipulus florum?

CN: The Janus search engine was designed to allow myself and other scholars to compare a medieval or early modern Latin text with the Manipulus florum. I named it after the Roman deity, Janus, who looks both forward and backward, because the search engine can reveal the influence of the Manipulus on texts written after its composition in 1306 and the influence of earlier texts on it.

When I conceptualized Janus, which was built by two computer scientists at the University of Waterloo, it was a ground-breaking innovation. We launched the search engine in 2008, and in 2010, a similar intertextual search engine for Latin scholarship was created in Australia. And then another appeared in Germany in 2015.

ES: How did you come up with the idea for the Janus search engine?

CN: Its inspiration came from turnitin.com. In about 2006, I was baffled by a student whom I had just caught plagiarizing. I had warned the class to not test the machine because the machine would win. And yet, one student cut and pasted large chunks of text directly from Wikipedia. As I pondered why that student would ever do that, I began to think of my own work. And then it occurred to me that that was exact kind of search engine I needed that could compare large texts to the Manipulus florum so that large bodies of text could be compared to the entire florilegium, which is why it is called an “intertextuality” search engine.

Once Janus was in place, I decided to develop other Latin florilegia for it; there are current three, and I have plans for more to be added to them.

ES: Did the use of digital tools and methodologies, and the Janus search engine, alter the trajectory of your career in research? Or did it facilitate an already existing research agenda?

CN: Nice question. I think both. When I added the Liber pharetrae to Janus, I thought it would be interesting to see how it overlapped with the Manipulus florum because I am certain that Thomas did not use the Liber pharetrae as an uncited source. We did an intertextuality report and found overlap between them, which then raises the question of what we really mean by a “commonplace.” That’s a research question that never would have occurred to me without the technology. Is a familiar quotation a “commonplace” because we see it and hear it often? Using the Janus search engine, we can say that, although the texts didn’t influence one another, there is still overlap. This allows us to get closer to what a “commonplace” really is because two, three or four different compilers of florilegia independently agree that certain quotations are worthy to include. The larger the database, the keener sense we have of the intellectual culture of the time. Since 2023 the Viridarium consolationis has also been searchable by Janus, and I intend to add two more Latin florilegia to Janus before the Auctores Project concludes in April 2026.

ES: Have you done any digital humanities work besides these projects on florilegia?

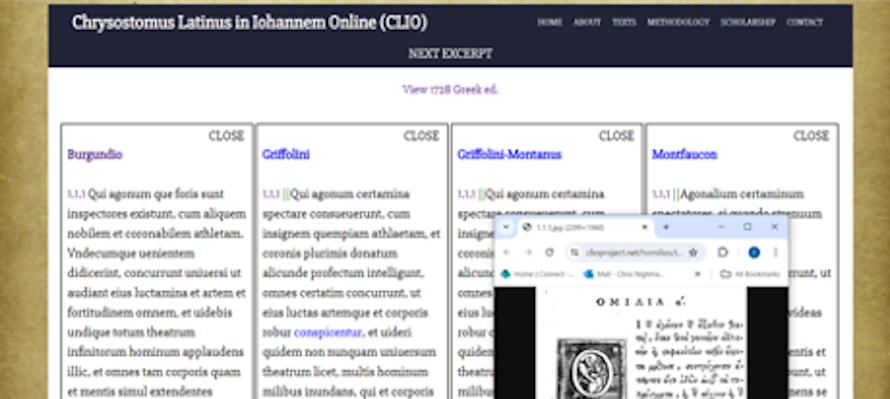

CN: Yes, about ten years ago I took a break from florilegia studies for a few years to develop a different online resource, the Chrysostomus Latinus in Iohannem Online (CLIO) Project. John Chrysostom was an important Christian saint of the late 4th century in the Greek church and patriarch of Constantinople itself—kind of like the Pope of the Orthodox Church.

Over the centuries his works were translated from Greek into Latin, and his commentary on the Gospel of John in particular was translated three times. The first was in the twelfth century and the second in the Renaissance. But the medieval translation was never printed because the Renaissance translation was printed in 1470, soon after it was created, yet the medieval translation had been very influential for three centuries among scholastic theologians. The third Latin translation was published in 1728. All three translations of the same Greek text are significantly different from one another. Actually, the CLIO Project now provides a fourth Latin version thanks to the pandemic, which forced me to cancel a conference panel and prevented me from acquiring copies of several manuscripts, so I used those funds to hire two student research assistants who helped me edit the heavily-revised version of the renaissance translation, which was published at Paris in 1556.

So what we’ve done for the CLIO project is present all four Latin versions of this text side by side so users can compare the various versions, and also look at the original Greek text from the 1728 edition, which we scanned from the copy in the Laurier Library.

Shortly before the CLIO Project concluded in 2022, I returned to my work on Latin florilegia with the support of a five-year SSHRC Insight Grant for The Digital Auctores Project that has so far yielded conference papers, articles and three new websites, as well as the enhancement of several of my existing online resources, with the assistance of a team of student research assistants.

ES: How do your RAs contribute to your work?

CN: Well, until a couple years ago my RAs basically just assisted me with editorial work by generating draft transcriptions from manuscripts or early printed books that I then developed into editions and bibliographical research, but recently I’ve enhanced the professionalizing my RAs who have been working on an early renaissance florilegium called Compendium moralium notabilium (Collection of notable morals). Over the summer of 2023 I supervised a team comprised of four undergrad and MA students from Laurier plus two PhD students from UW and Guelph who were each assigned one manuscript of Compendium that they compared to the printed edition of 1505, noting textual variants they found. For this work my collaborator on the SSHRC grant, Dr. Jeffrey Witt at Loyola University Maryland, trained them in XML code editing for his Scholastic Commentaries and Texts Archive, a big data open access resource. During the summer they worked remotely with manuscripts that had been digitized, but in the Fall term they travelled weekly to Toronto to do literal “hands on” work with an actual medieval manuscript of Compendium at the Fisher Rare Book Library and also do related bibliographcical under my supervision at the library of the Pontifical Institute for Medieval Studies. Over the past 20 years I’ve had about 35 student RAs funded by internal and external grants, most of which went to pay their salaries; all are acknowledged, of course, on the websites to which they contributed. I feel very fortunate to have stumbled upon a research field and methodology that has alllowed me to work with so many talented students over the years. I believe it is a often the case with digital humanities projects that they are well suited to student contributors; it certainly has been in my case.

ES: Do you think that printed books and journals are becoming obsolete as the digital modes of knowledge dissemination grow?

CN: This is a debate in digital humanities right now, and I’m on the side of those who feel that there will always be room for new printed books. In fact, I’m preparing one right now that is based on the CLIO Project. The earliest Latin translation of Chrysostom’s commentary on John from the 12th century currently exists on the CLIO Project as a transcription based on three manuscripts, but there are 16 surviving manuscripts of the text and I am preparing a full critical edition based on all of those manuscripts for print publication with a publisher in the Netherlands. Once that text is finalized, I will pay the publisher an open access fee that will allow me to update the text on the CLIO website to align with the printed text, but without the extensive scholarly introduction and the elaborate critical apparatus that will appear in the book. This has been my intention all along, as explained in my SSHRC proposals and on the website. In this case, the advantages of digital publication and the advantages of print publication are both very compelling, and I want the scholars who will use my work to benefit from both modes of dissemination.

Links to the websites mentioned in this interview: